Getting Started: How Every Student Benefits from a Strong & Diverse Network

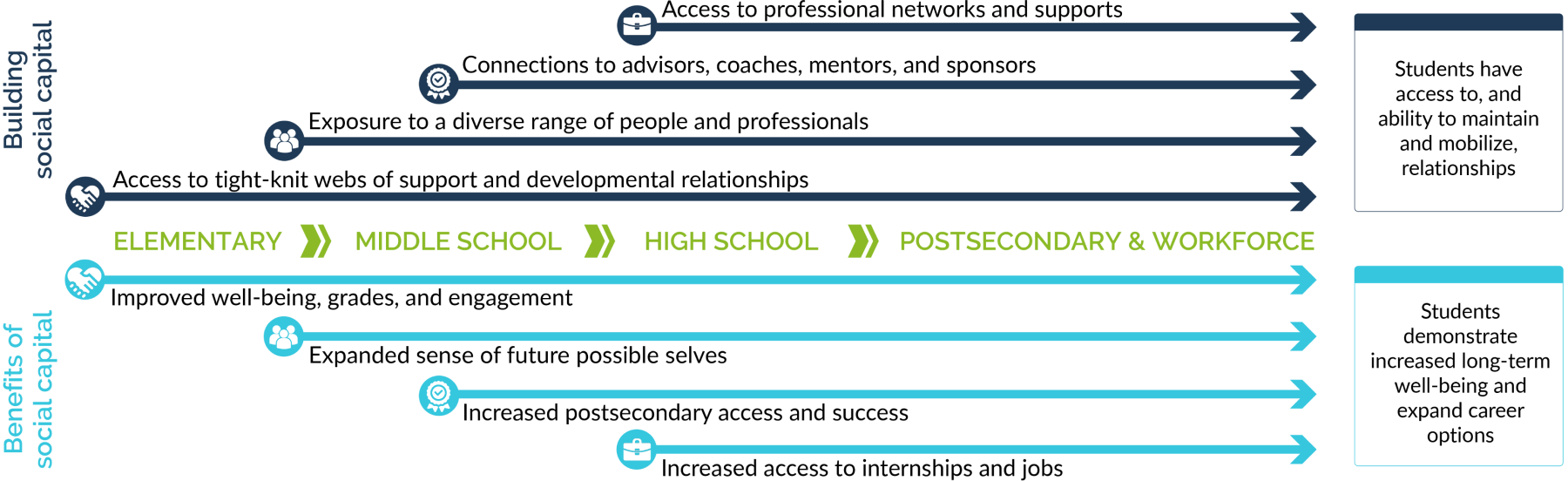

The value that resides in networks is what we refer to as “social capital.” Social capital is defined as students’ access and ability to mobilize relationships that help them further their potential and goals, both as those goals emerge and as they inevitably shift over time. The graphic below illustrates how social capital may manifest across a students’ journey in school and beyond, as well as the short- and long-term benefits of high-quality relationships in students’ lives.

All references and citations to the research and designs included in this playbook can be found in the PDF.

Go Deeper

Read The Missing Metrics report to learn how early innovators nationwide are measuring the growth of their students’ networks.

All students already possess social capital. They arrive at school with networks, and in the course of learning and serving students, schools and institutions contribute to those networks. However, slim but troubling data suggests that students’ access to relationships is not equally distributed and that not all relationships are supporting development and opportunity at an equal rate. A wide range of factors including race, family income, and parental education level can impact the size and scope of students’ networks, and the resources those networks can offer. Moreover, within K–12 and postsecondary pathways, students report unequal or limited access to developmental relationships, mentors, and professional connections. This can, in turn, impact students’ access to opportunity and economic mobility. For example, while 86% of adults in K–12 schools report that they are building strong developmental relationships with young people, only 45% of young people report experiencing strong developmental relationships. This data suggests that there is a stark discrepancy in how young people are actually experiencing relationships compared to how adults think or hope they are experiencing relationships. Among postsecondary alumni, fewer than half of students report having had a mentor in college, and students of color are 34% less likely to cite having a professor as a mentor compared to their white peers. Schools and institutions hoping to reverse trends like these have an opportunity in front of them: to invest in and measure students’ networks in more deliberate, equitable, and effective ways.

Note: Open the PDF to see a complete list of research citations.

Ensuring all students are growing and strengthening their networks

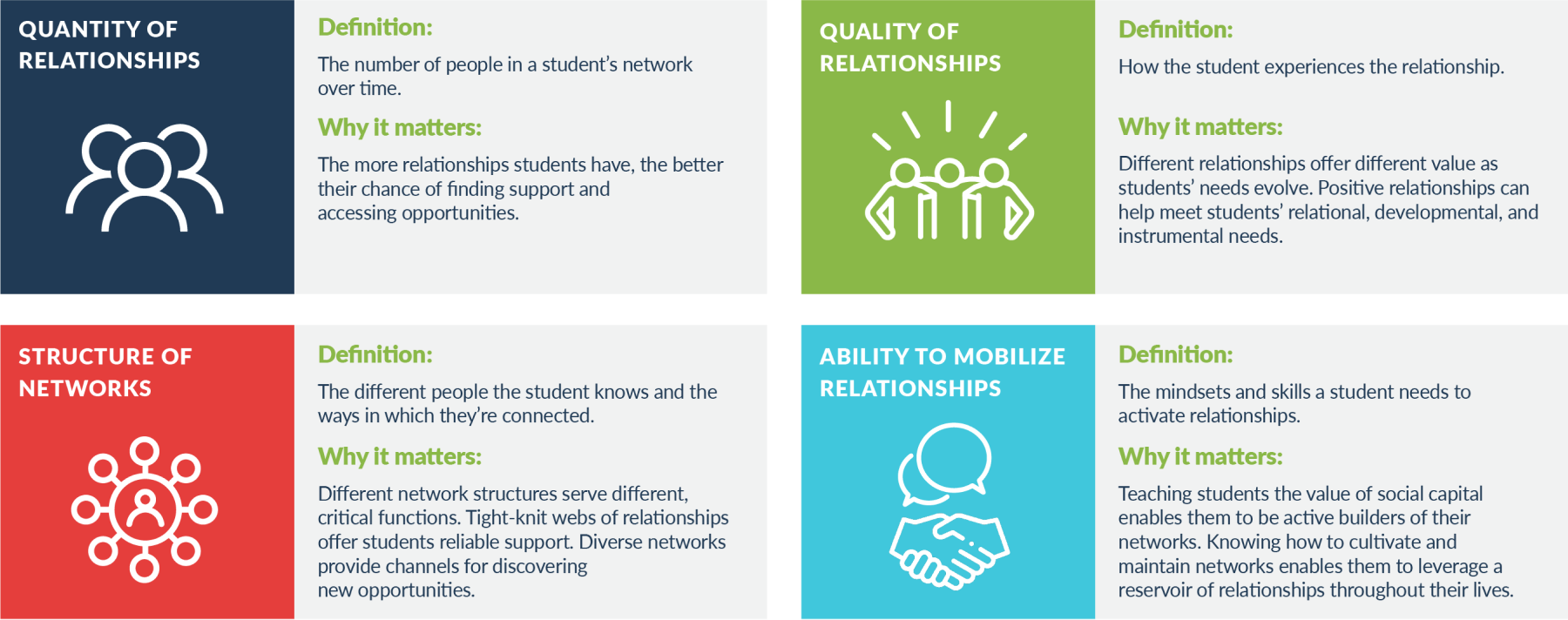

Opportunity gaps reflect resource and relationship gaps. But simply putting relationships within reach isn’t always enough to activate the benefits of social capital. In fact, a negative relationship can be worse than no relationship at all. Young people who experience negative or curtailed mentoring relationships show marked decreases in their sense of self-worth and academic ability. By taking a purposeful approach to measurement, schools and institutions can ensure all students feel supported and engaged on their education journey and graduate with both the skills and networks that drive success. Schools and institutions that are starting to prioritize students’ social capital rarely use a single metric to gauge how students access and experience relationships. Instead, these K–12 and postsecondary programs are capturing data across four interrelated dimensions:

A four-dimensional framework for measuring students’ social capital

Meaningful metrics to center equity in your design

Systems change will depend on educators and administrators sharing power and knowledge with both students and their networks. This will require schools and institutions to capture data that reflects the diversity of students served, and to equip students as agents of change in their own educational and professional pathways. As you navigate each design step, this playbook offers “meaningful metrics” your organization can use and adapt to ensure all students receive support and resources in the way they need.

As you consider what success looks like for your students and how you will measure progress, solicit feedback from the different members of your organization and community whom the data and vision will impact. Identify who needs to be included from both within and outside your organization to support planning, implementing, and progress monitoring of your efforts. To help ensure equity is infused throughout your efforts, reflect on how students’ identities are honored and integrated into your planning process from the beginning. This can include students’ racial and ethnic identities, socioeconomic status, and/or learning and thinking differences. A better understanding of students’ identities can inform how you are implementing relationship-building opportunities, collecting data on how students experience relationships, and defining success across your school or program. Specifically, in getting started, first ask:

- Why is this work necessary?

- Whom will this work benefit?

- Whom can this process hurt or harm?

- Whose perspective needs to be included in the planning phase?

- What does success look like for students? For staff?